Part 2: Rebuilding a $1M Ecommerce Business – Finding Products and Suppliers

In the first part of this series I discussed my strategy for building a $1m ecommerce and importing company within a year.

In Part 2 I am going to discuss what most of you are probably most interested in – how to pick products and negotiating with Suppliers. I can't stress enough though that finding products before selecting a niche is a huge error. Once you've selected a niche though hopefully this post gives you some good direction for finding products.

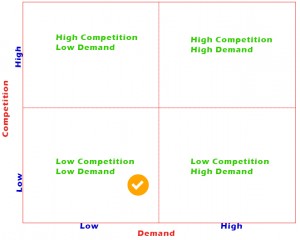

The Product Competition/Demand Matrix

When you're selecting products for your ecommerce company it's good to think of where your products fit on the Competition-Demand matrix above. In my experience, most new importers erroneously start on the High Demand-High Competition quadrant. Products like yoga balls and cell phone cables. These are the toughest types of products to be successful in and you should leave these types of products until you have very good experience importing products and selling on Amazon.

My strategy is to focus on low-demand items with low competition and with high price points ($50+). By low demand, I mean 1-3 sales a day. These products generally have lazy brand owners and are ripe to be picked off. In terms of the actual products, normally they have poor packaging, poor documentation, they're not fulfilled by Amazon, and they don't have any ‘easy differentiators' (i.e. product bundling, multi-packing, etc). Their marketing is generally just as poor and they have bad photography, bad descriptions, no advertising, etc.

Selling 1 product a day might sound really small, but if you do the math you can see that it's still possible to have a very sound company with this strategy.

Each Product = 365 products per year x $50 average price = $18,250/Year

100 Products = $18,250 x 100 = $1,825,000

Net Profit 15% = $1,825,000 * 15% = $273,750

100 products might sound like a lot, but keep in mind this includes all size/color/other variations. In reality, if you exclude variations, this number is well under 50 products and probably closer to 25 products. For example, my last company had 4 different types of ropes. Each type had about 10 different lengths/diameter. This meant there were technically 40 different variants arising from 4 parent SKUs.

Finding Products

In my niche, there are literally thousands of products. Our largest competitor owns hundreds of brick-and-mortar stores. As I've mentioned, my goal is to ultimately find around 100 products. You can see the importance of finding a niche. Without a niche, finding 100 products sounds daunting. But when you have a niche with thousands of products, finding 100 sounds much more manageable. But regardless, to find 100 products I needed to first start by finding one product first.

I had a few criteria for my first product:

- I must be able to differentiate it, either through physical changes or marketing

- It should be over $50 Retail

- Limited optimized competitors

You Either Need to Make Your Products Better or at Least Make Your Customers Believe Your Product is Better

Here's some bad news: strict private labeling is dead. Finding a product in China and putting it on Amazon for a cheaper price than your competitors is no longer a sustainable business model.

To succeed you either need to make your products better or at least make your customers believe your product is better. There are easy ways to make products better and difficult ways to make them better. The latter involves actually making design improvements to a product. That's really hard and outside the skillset of most new importers. There are easy improvements you can make to a product. We go into all of the ‘easy differentiators' in our Importing and Developing Kick Ass Products course but one of my favorite ways is to bundle products.

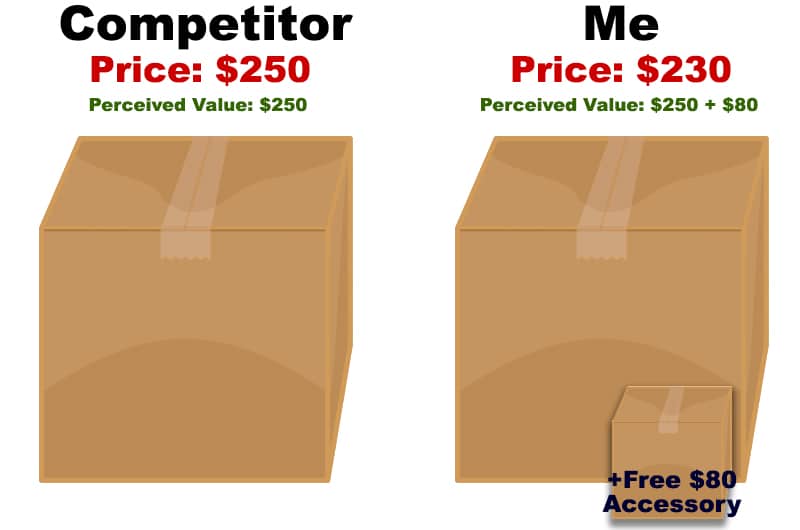

For the product I ultimately chose there was an accessory that all of my competitors offer separately to the main product. The accessory is about $80 retail (compared to about $250 for the main product). My cost on the accessory is $25.70 while the actual main product cost is $77.60. My goal was to offer our product about 10% below the price of my cheapest competitor AND offer the free accessory.

Being 10% cheaper than my competitor might be enough to win some customers but typically you need to be 25% cheaper than the next cheapest guy to win most customers. I could probably price myself 25% cheaper but the problem when you do this is that it's only a matter of time before a competitor comes in cheaper. Cost leadership is a strategy, price leadership is not.

Now by offering the free accessory most people will choose my product priced at $230 with a $330 perceived value over my competitor's $250 product. Yes, a competitor could come along and offer the same bundle as me but that takes a lot more effort than just dropping a price on Amazon.

There are times when I don't even need to make a product physically better – I can simply make it have the impression of being better even though it's identical to my competitors. 1 Picture/1 Line Description Amazon Listings are prime targets for such differentiation. For my former company, we used to advertise many of our products as being “Constructed from Marine Grade 316 Stainless Steel”. My other competitors simply had one bullet point that said “constructed from stainless steel” even though they used the exact same material. If you were a boater, would you risk buying the product that you weren't sure was “marine grade”? There is a lot of meat on the Amazon bones for marketing differentiation.

It Should be Over $50 Retail Price

I want most of my products to sell for over $50. There's a couple of main reasons for this philosophy. First, the cheap $10-20 items, which normally have product costs of $1-2, attract a lot more competition than the higher priced items. These items require a couple thousand dollars or less of capital to get started and have relatively smaller barriers to entry in this regard.

Second, Amazon is now predominantly a Pay to Play marketplace meaning you have to spend a lot on PPC Sponsored Ads to get real results. If a $200 item has a $0.50 cost per click on Amazon it doesn't mean that a $20 item has a $0.05 cost per click. In fact, costs per click seem to be relatively the same no matter the cost of the product. So if I'm paying $5 to acquire a customer, I'd much rather do it on a $200 item where I'm making $30 in net profit than a $20 item I'm making $6 in net profit on.

Limited Optimized Competitors

This is something we go into more detail on in our course and in this article but in summary I am looking for products with few, if any, optimized competitors. So many people when they are first starting are looking for products with no competition and they got stopped in their tracks when they find that these products don't exist. Don't even bother looking for products with no competition – all products have some competition.. Instead, look for products with little optimized competition.

There are tons of these product categories. Categories where the top competitors have 1 photo, limited bullet points, 1 line descriptions, don't utilize paid advertising, and (the granddaddy of all) they don't use FBA. These are the product categories where there is still a lot of meat on the Amazon bones left.

The big question is, what do I consider limited competition? In my niche, ideally I want to see no more than 3 optimized competitors. In fact, ideally I'm looking for no optimized competitors at all.

Selecting my Product and Improving It

I finally narrowed in on my first product, a vehicle accessory used for camping. This particular item retails for close to $300 from the 3 main competitors on Amazon. It's a large over-sized item which I know will keep a significant portion of the competition away that is afraid of shipping via sea freight.

As mentioned above, one of the main differentiators I did for the product was bundling it with a popular accessory. However, I also did a few other things:

- Changed the fabric to a different color and a slightly higher quality material

- Changed the zipper from a low quality zipper to high quality zipper

- Changed the box from brown to white and included a high-quality colored sticker on it

- Included high quality instructions with each item (written by me)

I didn't re-invent the wheel by any means but I definitely made the product overall marginally better than the competition. Remember, in an ideal world Amazon and consumers don't reward better marketing, they reward better products. Not to beat a dead horse, but making your products better so they are sustainable long term is the main focus of our Importing and Developing Kick Ass Products course.

I should mention that the first thing I do whenever I develop a product is to buy the best selling competitor off of Amazon. I want to see exactly what they're doing an improve on it.

Finding and Negotiating with Suppliers and Production

I went to Alibaba to find my Supplier for this product. I don't particularly like Alibaba and normally I prefer Trade Shows to find contacts. However, I'm new to this niche and I haven't had the opportunity to explore any relevant trade shows yet.

After talking with a few Suppliers I honed in on one Supplier. Once I had essentially selected this Supplier to do business with for my product I asked for a sample. I asked for a sample not only to verify their quality but also as a negotiation strategy. Suppliers get countless tire kickers inquiring about products. By ordering (and most importantly) paying for a sample it demonstrated to this Supplier I was serious. Suppliers are more inclined to give a better price to a demonstrably serious buyer, which they ultimately did.

Shortly after receiving the sample and agreeing on pricing I placed the order with my Supplier by putting 30% down.

I timed my order to be completed to correspond with a visit I was making to Beijing in the Spring. Doing quality inspection checks is critical, especially the first one or two times working with a Supplier. Doing an inspection in person is the best way but obviously not reasonable most of the time. For all of the other times, I would simply pay the $300 or so for an inspection to be done through Asia Inspection.

The inspection went well and there were no major flaws. There were a couple of small problems, particularly with the logo printing but they weren't significant enough to hold up the order.

Conclusion

In late May my goods finally shipped out of China and they were finally received at my 3PL in early July. The month or so transit time was slightly longer than normal but not by much. From the time I first talked to my Supplier and the time I received the final goods was nearly six months. Six months is a fairly standard development time for a new product in my experience. Importing from China is by no means a get rich quick business (I'm not sure if such a thing exists) but it is still a very profitable business to get into as I'll show in the final part of this blog series when I share my initial results and sales figures.

What has your experience developing products been? Does the entire importing and development process take months for you or is it significantly shorter or longer? Share your thoughts and questions in the comments below.

Hi Dave

Cool series. Will be following.

Rgds

Thanks!